Recent Articles

- Weekly Roundup, December 19th June 25, 2015

- Weekly Roundup, December 12th June 25, 2015

- Weekly Roundup, November 28th June 25, 2015

By Erica Garcia, Curriculum and Community Coordinator, National Hispanic Cultural Center

This 2014, each of the participating sites in the National Dialogues on Immigration project will be contributing to our blog post series, “Immigration: Our Stories.”

As a young girl, I was aware that generations of my family were from New Mexico dating back hundreds of years. Our family takes great pride in being Nuevo Mexicanos. By middle school, I started questioning that strong sense of identity when I noticed my Grandmother would say, from time to time, that we were “puro Españoles.” Our language, and traditions connected us to Mexico and yet I was still your typical “All American Girl.” In college and as an adult I had the opportunity to pursue these lines of identity and reconcile a greater pride than the fractured one I had as a girl and embrace a deeper sense of identity. An identity based on major shifts in culture, history, and politics all of which have been rooted in immigration.

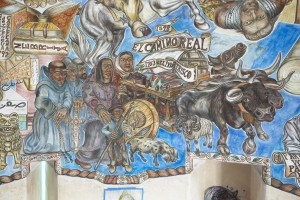

Immigration and migration have always been part of our humanity, our survival, and our development as a larger society. Yet, throughout the history of what is now the United States that most natural part of our survival has been treated as unnatural, negative, and illegal, for some. The National Hispanic Cultural Center and our Dialogue Program (Ex)Change has used a work of art titled Mundos de Mestizaje to demonstrate the impact of immigration throughout the 13,000 years of Hispanic history culminating with the cultural layering and diversity of New Mexico today. Our dialogues look at the full impact of immigration, language development, advancement in the sciences and humanities, medicine, art, music, family and community. So far, the best way we have managed to get to a place of dialogue is by asking three basic questions:

· What 5 adjectives would you use to describe an American?

· What 5 adjectives would you use to describe yourself? (The group shares their answers and then the third question is asked.)

· What does an American look like?

The group is then exposed to the artwork, a 4,000 sq/ft buon fresco. This work demonstrates the impact of migration patterns in the southwest and northern Mexico dating over 10,000 years. Some of those trails were stitched together by Europeans for the Spanish Crown creating the Camino Real. This difficult, and hard to travel road extended 1500 miles between New Mexico and Mexico City, making the presence of the Spanish colonies possible.

The Spanish Camino Real (1598-1821) was the only way into the New Mexico area. Immigrants from the east, who dared trespass into Spanish territory, were considered “illegal” and were generally arrested as spies. For example Zebulon Pike was arrested in 1806 because he was believed to be a spy. There were various times of peace and friendship then intolerance and strife between dozens of cultural groups.

With Mexican Independence (1821) came the desire to develop economically. The eastern Spanish borders were opened up via the Santa Fe Trail, which connected New Mexico to the United States. Immigrants from the east were welcomed into New Mexico (Mexico) and merchant families from the U.S. and Mexico began to intermarry as the economy flourished. Many Native American groups, mostly non-sedentary also migrated, depending on the seasons and available resources throughout the plains. Later, as the United States expanded to the west, tensions developed between Mexico and the U.S., which ultimately culminated in the Mexican American War, which changed the southwest and the west forever. New Mexico became a territory of the United States and once again allies and extended families were divided by racism and religious intolerance.

When the railroads came in, immigration was great. When the Depression hit, immigration was bad. And, when there weren’t enough laborers, immigration was good. Such extreme movement always comes at a price. Sometimes it is financial, other times it is about leaving family behind, and risking violence while hoping for a better future.

This is why questions number two and three are so important. They help our visitors understand that each and everyone of us has had to risk something at some time for a “better life.” These questions also help us see our community as a diverse blend of people and histories. Through these basic questions, we are bound to find common ground. The questions move the focus away from immigration to the question of “why?” Why do people emigrate? The group realizes no matter what our backgrounds may be, skin color, or how many generations we’ve been in this country we want the same thing: to live a quality life.

Quite naturally, the conversation leads to resources. Everyone can “get” someone wanting a quality life, but is there enough for everyone? Maybe because we are in New Mexico, the focus tends to shift to Mexico. NAFTA will come up, but not the long political and financial history between the U.S. and her southern neighbors. We know not all immigrants come from the south, and the majority of those individuals are not Mexican; but somehow that’s where our “immigration gaze” turns. The Wall becomes a topic and then national security. And then we get back to the question of why. Why do people want to come here? Generally, there isn’t time for much more. The groups become saturated, I am usually exhausted, but there is a soothing sense to the end of a dialogue. An understanding, even if for a short while, that no one is “out to get” someone, hurt anyone, or take anything away.

After, I think about a second dialogue – the dialogue that happens when everyone goes home – I get curious. Are they loud, quiet? I often wonder how those who participated in these dialogues view other people they see on the street on their way home. Is it different? Has their experience with us altered how they see their friends, neighbors, or new people they meet? When I think about these things it is always positive and each time I am filled with more hope for our future.